In observance of the 2025 Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays, the BND Institute of Media and Culture is proud to recognize the life and legacy of renowned chef and cookbook author Edna Lewis. Since 2018, the BNDIMC has paid homage to Ms. Lewis’ gift and work through its annual Kitchen Talk series. Only in recent years has Ms. Lewis’ talent in developing recipes and menus and cooking mouth-watering meals —from a farm in Freetown, Va. to the bright lights of New York City and beyond — been acknowledged by wider audiences. We are thrilled to continue telling her story. Bon appétit!

Preserving the legacy of Edna Lewis is a ‘charge to keep’

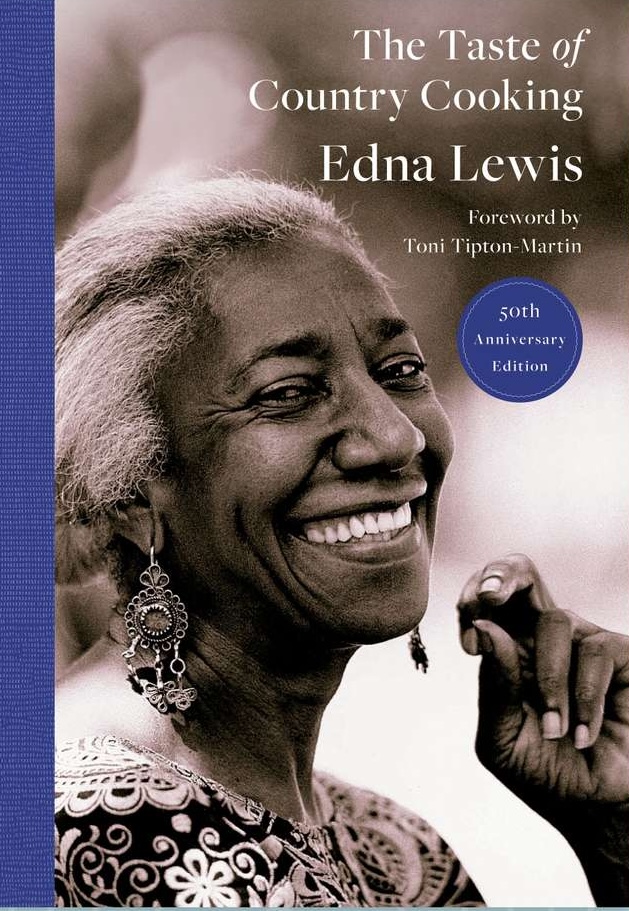

The 2025 Family Reunion, hosted by Kwame Onwuachi at Salamander Resort in Middleburg, Va. last August, included author and documentary filmmaker Deb Freeman (left holding platter during a family-style luncheon). Freeman delivered remarks for a panel discussion about renowned culinary chef Edna Lewis (right). Photo of Deb Freeman by Clay Williams.

By Debora Timms

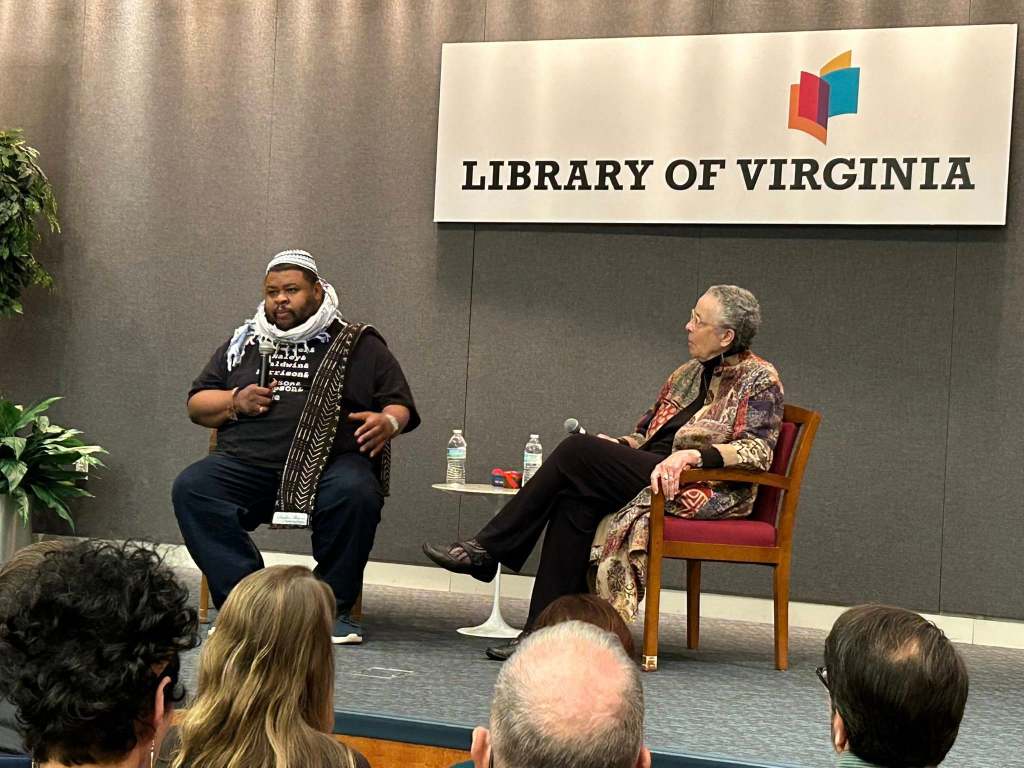

Black women have been an integral part of American food culture without the visibility and acknowledgment of being credited for it. This fact was explored during “Edna Lewis and the Legacy of a Black Woman Chef,” a roundtable discussion on Aug. 16 as part of the Salamander Resort’s Fifth Annual Family Reunion in Middleburg, Va.

Born in 1916 in Freetown, a rural Virginia community founded by formerly enslaved people, including her paternal grandfather Chester Lewis, the young Edna Lewis’s family taught her how to cook with food that was locally available. She left the farm for New York as a teenager, and would go on to become a trailblazer.

At a time when Black female chefs were rare, Lewis became the chef and partner in New York’s celebrated Cafe Nicholson in 1949, then went on to cook in other elite restaurants in the years that followed. By presenting the food and traditions of her childhood with simplicity using beautifully fresh, in-season ingredients, she redefined Southern cuisine and became an early pioneer of the “farm-to-table” movement that later exploded into a mainstream phenomenon in the 2000s.

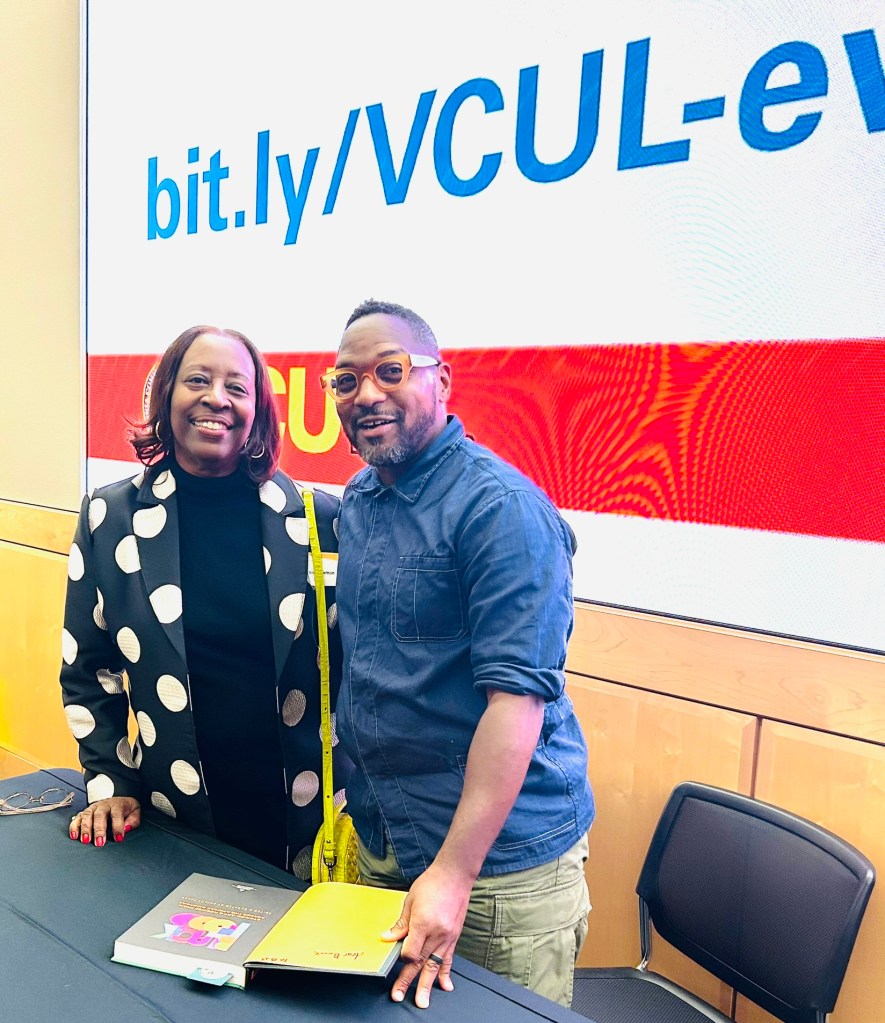

Freeman is a writer and host of the podcast, “Setting the Table,” as well as executive producer of the award-winning PBS documentary, “Finding Edna Lewis,” which explores the life of the late chef and cookbook author. Freeman, who alos was born in Virgnia, provided an introduction and overview of the acclaimed chef’s life at Salamander last summer.

Southern food often has suffered a bad rap, she said in a recent interview with the BND Institute of Media and Culture.

“Edna Lewis turned that on its ear,” she said. “She got people talking about Virginia food and until then, it was often left out of the American conversation.”

The partnership at Cafe Nicholson certainly profited from Lewis’ talent and cooking skills by promoting her food, but not her. While she may have been instrumental in bringing Virginia into the culinary conversation, Lewis herself remained in the shadows.

During the Salamander panel discussion, moderator Cheryl Slocum, a James Beard award-winning writer and editor for Food & Wine magazine, asked author and culinary historian, Dr. Jessica B. Harris, as well as chefs Mashama Bailey and Carla Hall about their knowledge of Lewis. None could say they grew up knowing her as a household name, and it wasn’t until they started searching that they became aware of her. This even though the second of her four cookbooks, “The Taste of Country Cooking,” is considered a classic.

“I mean, I went to a French culinary school where Black women, Black people were not the focus,” Hall said. “You have to really dig and be intentional about finding them.”

Harris referenced an old Methodist hymn in declaring the responsibility to carry Lewis’ legacy forward “a charge to keep.” That intentionality is something each of the participants said they strive to give voice to in their lives.

Bailey does so as the award-winning executive chef and partner in The Grey, her restaurant in Historic Downtown Savannah, Ga., where female culinary influences such as her mother and Lewis inspire her cooking, and as chairwoman of the board at the Edna Lewis Foundation which works to honor and extend Lewis‘ legacy by creating opportunities for African Americans in agriculture, culinary studies and storytelling.

Other recognition has come since Lewis died in 2006.

Lewis was named an African American Trailblazer by the Library of Virginia in 2009, and was depicted on a U.S. postage stamp in 2014. In addition, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources unveiled a historic marker near her hometown in 2024.

However, Hall noted the need to be “be out there making her a topic of conversation.”

During her phone interview, Freeman addressed why these types of conversations are critical.

“So much of our history is oral, not written. Once it’s gone, it’s gone,” she shared.

For the past decade Freeman has used her writing and her podcast to explore Black foodways and the intersections of race, culture and food.

“Our ancestors had their language and their names stripped from them, but their legacy of food remains,” she continued, adding that this legacy is made up of the cooking techniques, seasonings and spices that create a direct link to the West African heritage of the past.

“If we are not documenting it and taking note, we’re doing a disservice to that ancestral past, but also to our more immediate family, our parents and grandparents.”

Freeman added that while it is heartening to see increasing numbers of Black writers and archivists, but stressed that more are needed because the work is “very difficult when there are not names and written documents to connect the dots.” Lewis’ legacy comes alive in these chefs and storytellers. But it also lives in every kitchen and every story that connects food to identity. Her work serves as a guide and a challenge – to cook with simplicity, to use beautiful food, to celebrate community and to honor those who laid the foundations. By doing so, the vision